Which Came First: The Play or The Design?

Updates on the second week of rehearsal and a behind the scenes look at how design elements for the production were developed.

Independent theater provides opportunities for artists like myself to bring unique and groundbreaking work to life, offering a stage for voices that might otherwise remain unheard. By championing independent theater, you can nurture a vibrant ecosystem where creativity thrives and varied perspectives enrich the performing arts.

During the second week of rehearsals for the adaptation of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel WE that I am directing and producing, I worked through nearly all the material in Act I and seventy percent of the scenes in Act II. There’s two shadow sequences and one movement piece to put together in Act I and six short scenes to stage in Act II; then I’ll have touched everything in the play.

Act I still feels too long. I noticed the length when we worked through the entire act this week. Its lumbering pace became more pronounced when I moved on to Act II which, by contrast, glides along with speed. Now that I’ve seen both acts, I’d like to explore how I can infuse the first act with the momentum of the second.

Although I’ve been anxious about the length of the play, I received some welcomed encouragement from one of my collaborators this week: he advised me to worry less about the length and to focus more on developing the play as intended. I can make a determination about length once I’ve seen the whole thing. It was a good reminder that now is the time to revel in the glorious duration of this overstuffed creation because we are still exploring ideas. We have to try the ideas first and edit later–once we actually see what the ideas are.

We are building toward a stagger-through of the entire show at the end of week three. Based on the progress we’ve made, I’m confident we will have a rough draft of all (or most) of the show to present to a small, invited audience next week. This is good news because we want to see the entire play in one sitting so we can reflect on what’s working, what needs revision, and what needs to be cut before our final rehearsal period in September.

Another reason for running the entire play, even in rough form, is to let the actors experience the work as a whole instead of a potpourri of isolated scenes. If you’re a theater director, you may have had the experience of working with actors for hours on one scene, and by the end of rehearsal, that one scene was alive with electric performances. When you later put that vibrant scene in a sequence with the scene that comes before it and the scene that goes after it, all three scenes fizzled. While it can feel like the previous work went out the window, I’ve learned that’s a perception rather than a reality. The exciting work didn’t evaporate, everyone remembers it well, what’s happening is the actors need to feel what it’s like to act through all three scenes, which is a different task than acting one scene in isolation. As a director, it’s hard to watch that happen, but when it does I sit on my hands and let it roll; I know everyone simply needs time to re-orient themselves. The electricity will come back, even more charged than before, it just takes time. For that reason, the sooner we can all experience the play as a whole, the sooner everyone can wrap their brains around how the piece works, and the journey their characters take over the course of the play.

Design Elements in the Rehearsal Room

In addition to acting, the ensemble is moving six screens around the stage. As shown in the rendering above by scenic designer Yang Yu, the production features screens on wheels that function as both projection surfaces for images or video and as shadow puppetry screens.

As I’ve learned from experience, if actors are going to move anything in the show, they need to move it as part of rehearsal. I don’t wait until technical rehearsals the week before opening to introduce moving set pieces–bringing in new elements in the eleventh hour overloads everyone’s brains and grinds the tech to a halt. However, since the set is not built yet, we don’t have the scenic pieces to practice moving, so we need a work-around.

In rehearsal we have what I call “do for now” versions of the screens. They are about the same width and a foot shorter than what we expect the final version of the screens to be, but they will do for now, because the actors get hands-on experience moving something similar to what they will move in the show. Having the “do for now” screens in rehearsal also gives us the opportunity to experiment with what these screens can do. We found we can move them slowly around characters to create surreal environments or a sense of dramatic tension that expresses the feelings of the main character. The screens are fun to play with and when they all move at the same time it feels like watching a ballet of screens!

The idea for the screens was developed years ago, well before a draft of the play was written.

In the summer of 2022, I met with designers to talk about why I wanted to put this novel on stage and to brainstorm how we might use theatricality to express the story’s narrative and underlying themes. Dystopian science fiction novels are most often adapted for film and video because special effects artists can realistically depict space ships flying through the cosmos or a massive armies of alien invaders. But in live theater, there’s no adding CGI in post production, and the more we try to realistically show space ships and aliens, the worse it’s going to look in front of a live audience–they will know it’s phony.

Instead of trying to realistically show sci-fi moments, my design collaborators and I thought about how we could artistically suggest the otherworldly elements of the story in a way that can only be done on stage.

In the previous production I adapted and directed, we used video projection on the back wall of the theater and on a downstage translucent curtain. Rather than repeat that technique, we wanted to push ourselves forward, so we decided to project on the back wall again, but instead of the downstage curtain, we decided to use six moving screens.

The story takes place in a city surrounded by a massive glass wall. We can’t build a glass wall in the theater but we can use the screens to express the shape of the wall and project images onto the screen to illustrate its glassy texture.

The novel has scenes that take place both inside and outside the city. We can’t build a set that has all of these areas, but we can move the screens around to delineate space and make it feel like we’ve gone to a new setting within the story.

We want to project more than just static images. As shown in the video clip above1, we used flashlights and green bottles half-filled with water to evoke the feeling of a flowing river. Our projection designer captured the effect on video which can be digitally manipulated to enhance the effect.

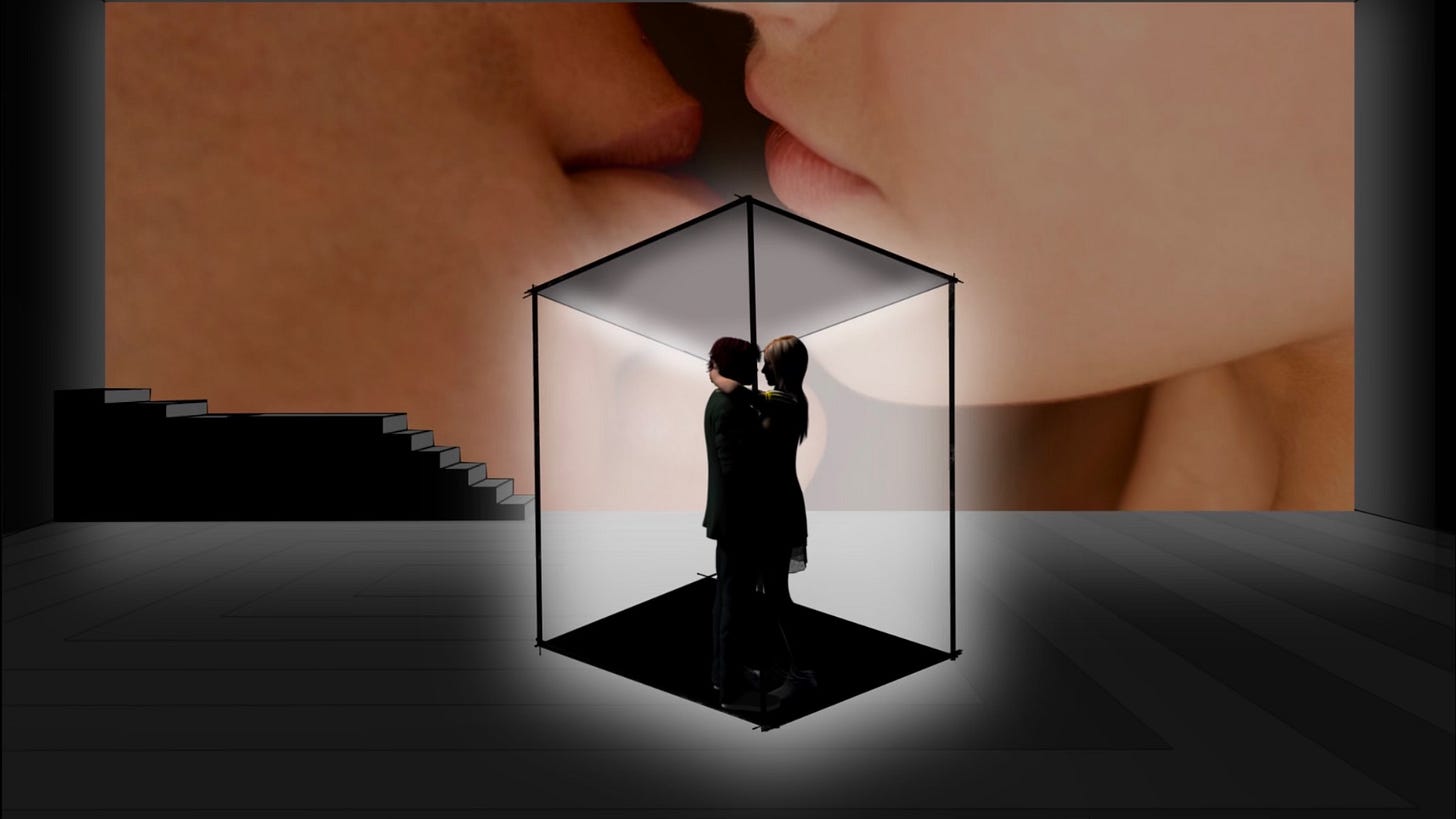

As I wrote about in my previous post, we will also use the screens during moments of intimacy which we may augment with recored video on the back wall.

Throughout the novel, the main character talks about the “heavy hands” of the state leader. As seen in the above rendering, we can magnify the character’s “heavy hands” either through projection or shadow puppetry.

These renderings are design concepts rather than concrete storyboard illustrations–they express the idea we aim for. I expect the final product will look different than what is shown in the images. But these renderings have been vital to the development of the play and I’m looking forward to seeing what the screens look like on opening night.

We’re off for the next two days, but will be back at it later in the week.

Thank you for reading. I’ll keep you posted on how things progress and I look forward to seeing you at the theater October 11 - 20, 2024.

I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For

Click here for WE tickets. Performances October 11 - 20, Brooklyn, NY.

WE is made possible by grant funding from the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR) in the Arts, the Puffin Foundation Ltd., and NYSCA-A.R.T./New York Creative Opportunity Fund (A Statewide Theatre Regrant Program). Production design support provided by the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Design Enhancement Fund, a program of the Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York (A.R.T./New York).

This video also features music composed for the production by Ian McNally.