Joy, Fulfillment & Wonder

The rewards of making theater through a collaborative process

CIndependent theater provides opportunities for artists like myself to bring unique and groundbreaking work to life, offering a stage for voices that might otherwise remain unheard. By championing independent theater, you can nurture a vibrant ecosystem where creativity thrives and varied perspectives enrich the performing arts.

On the drive home from the final summer rehearsal, I laughed so hard I could barely breathe. In the car, my collaborators and I roared over a line of dialogue an actor improvised during the last run-through of the play. When this actor forgot his line, the one he concocted was so clever, true to the character, and authentic to the voice of the Russian author whose novel the play is adapted from, that it stopped the run because everyone burst into astonished laughter. To top it off, the line was far more hilarious than anything Yevgeny Zamyatin wrote in We. It was brilliant! As we laughed together in the car I thought, “This is why I do this work.”

Making theater isn’t always laughter, nor should it be. In his musical Sunday in the Park with George, lyricist and composer Stephen Sondheim wrote, “Art isn’t easy.” He was right. As I lamented two weeks ago, this project hasn’t been entirely smooth sailing. But, the time, effort, concentration, risk, resourcefulness, skill, diplomacy, patience, calculation and commitment required of any artist attempting to produce and direct theater in New York City is what makes the endeavor rewarding. The up-front costs of art-making may be high, but the return on investment pays handsomely in joy, fulfillment and wonder.

Many of these returns are dispensed on opening night, when my directing work is done. On that night, I’ll sit in the audience and watch the show, knowing what’s on stage is there because my collaborators and I created a work of art that didn’t exist before we valiantly ventured into a rehearsal room.

But there are many rewards along the way to opening. While assessing the work achieved so far in preparation for production meetings with my design collaborators, this week I reflected on the abundance of joy, fulfillment and wonder I experienced this summer.

The Joy of Handing Over the Creative Reins

I came to theater directing by way of teaching. When I’ve put together shows in educational settings, I’ve taken on all the job roles: directing the play, choreographing the dances, building the sets, finding the props, sourcing the costumes, creating the sound effects, making the poster, the list goes on. In many ways I enjoy the multi-tasking that comes with teaching because I learn new things. I also acknowledge it can be taxing and at times thankless.

With over two decades of experience wearing all the hats while teaching, I sometimes have a knee-jerk impulse to do everything because the reptilian side of my brain thinks, “If I don’t take charge of each task, nobody else will and it won’t get done.”

But in my professional theater work, I have to put my inner lizard on sabbatical. In the theater, not only do I have the luxury of generous, talented collaborators who take the reins of the creative tasks that are beyond my expertise, I experience the joy of witnessing their masterful artistry. They conjure creative solutions to artistic conundrums that exceed my wildest dreams.

One skill theater directors have to learn (over and over) is knowing when to get out of another artist’s way and trust the job will get done. Sometimes the best outcomes happen when I make a plan with a design collaborator, then walk away and let the designer work with actors alone.

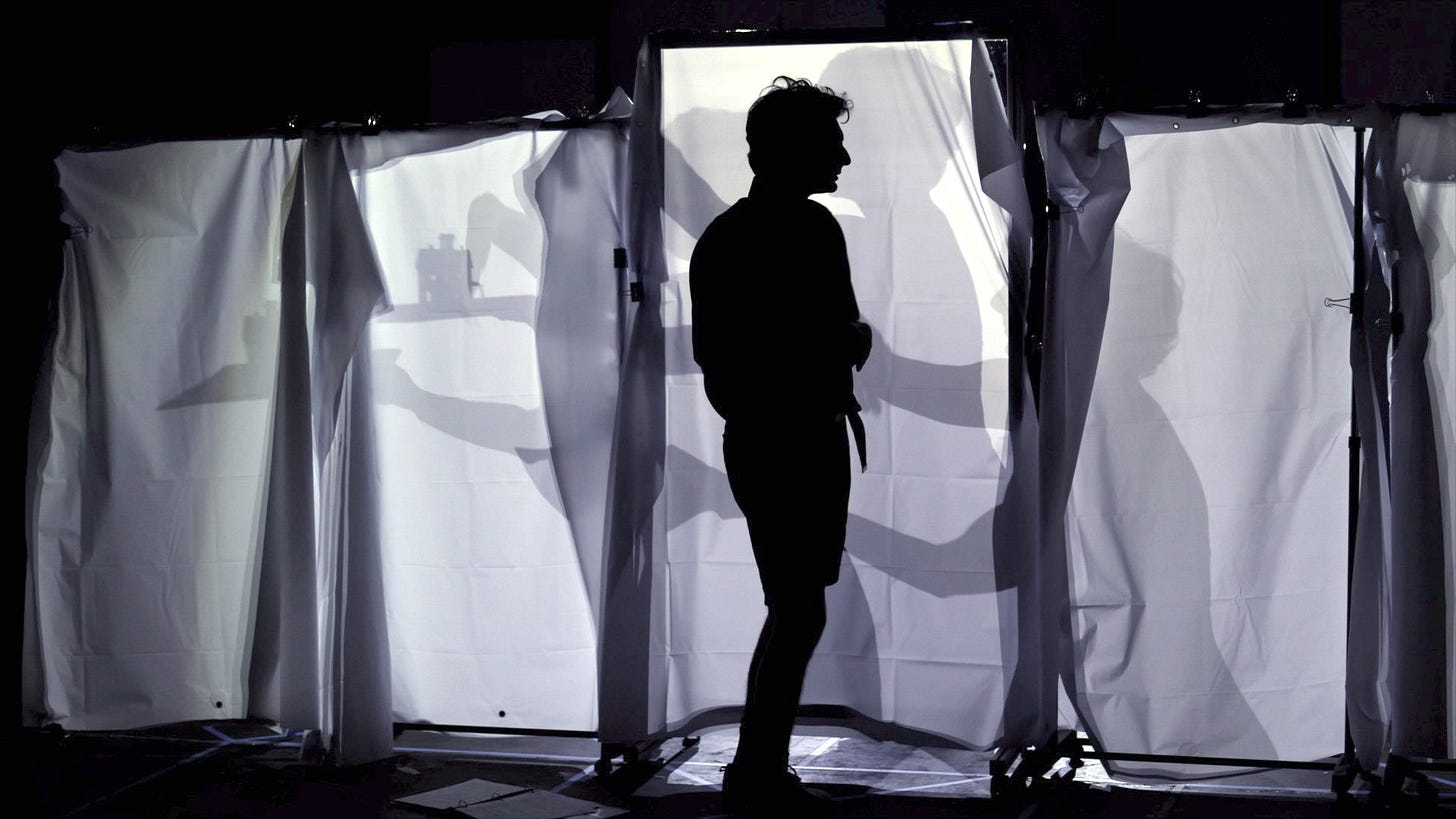

A highlight of the summer happened when our shadow puppet director and designer came to rehearsal and created the dream sequence pictured above. In our planning, we decided the dream would be made from objects one character recalled from an earlier scene. The actors showed the scene to our shadow puppet director who watched it to observe the various objects we incorporated in it. When they finished I asked, “You got it?” She said she did, so I walked away and left her alone with the actors. When I came back, I experienced the joy of a newly devised, haunting dream cast in larger-than-life shadows appearing and dissolving like jungian phantoms.

I marveled at how quickly the sequence was created and giggled with joy as our shadow puppet director walked out the door thinking, “She was here for less than ninety minutes! That’s artistic mastery combined with an efficiency I’ve never seen!”

I was also bouncing off the wall with joy because a beautiful moment was made for the show by someone other than me! That’s not because I shirked my responsibility, it’s because I made the effort to create time and space for another artist to shine.

The Fulfillment of Building a Collaborative Ensemble

The actors in this production were not cast through auditions. That’s because auditions don’t tell me if an actor has the skills required to collaboratively create a play through a process that works best for me.

Auditions show if an actor has talent and exudes the essence of a role, but they don’t tell me if an actor has the temperament to dive into rehearsing a play that isn’t fully developed and will change numerous times. I can’t tell from an audition if this actor can gracefully discard an idea after spending hours developing a character or moment.

For readers unfamiliar with new play development, a typical process includes what’s called a “play reading.” In a reading, a playwright brings in a draft of the script and a director works with actors positioned behind music stands reading the text of the play. After a day (maybe two) of rehearsals, an audience comes in to “hear” the play. While hearing the play out loud can help a playwright identify whether or not the dialogue sounds authentic or if the dramatic structure of the play works, it doesn’t tell me, as a director, how the play moves in time and space and it doesn’t tell me if the piece is alive with theatrical imagination.

For that reason, I jettison readings. I develop a play in a workshop style, on its feet, in the room with actors and designers. This way, I infuse the piece with the language of the stage which includes the text but also the movement, sound, gesture, scale, music, lighting, projection, costume, puppetry and other theatrical elements through which I express the play. That’s not a typical approach to new play development, and if you don’t cast with that in mind, you could unintentionally provoke reactions from collaborators that are not useful.

In his memoir about directing Sunday in the Park with George, James Lapine vividly depicts the aggravated resistance he experienced from some actors in the company while developing the show in an unconventional workshop setting. Even Hal Prince, one of the most skilled directors who ever lived, tangled with actors who resisted cutting material as shown in this documentary about the 1980 London production of Sweeney Todd. In collaboratively created work, temperament is as important as talent, so I cast actors with both qualities in mind.

Instead of auditions, I called actors I’ve worked with before, actors I’ve met but haven’t worked with, and actors referred to me by colleagues familiar with my process. I met each actor individually for about an hour to talk through the project and how I planned to work on it so they could decide for themselves if they wanted to join the show or not. When I explain to people what they are signing up for before they agree to join, people usually say, “Yes!”

Among this cast are former professional collaborators, former graduate school classmates, and actors who were undergraduates when I was earning my MFA. One actor was cast because the ensemble from my previous production met him at a restaurant around the corner from the theater and invited him to the prior show, another actor I met when she was a high school teacher and I was a visiting teaching artist in her classroom. There’s even an actor in the cast who I worked with at summer camp when he was seventeen! Some days I looked around the room and thought “Am I in an episode of This Is Your Life?”

I cast well. I know that because I see how supportive and encouraging the actors are to each other, to the creative team, to the production stage manager and to me. I see how they spread bravery around the ensemble by taking creative risks with their acting choices. I experience their willingness to try new things and discard ideas that aren’t useful. I see their delight when our shadow puppet director gives them flashlights to play with in the dark. I see them relish time in small groups creating moments of theater with each other and proudly bringing those moments back to perform for the whole group. As I wrote in a previous essay, I’m not the only one who’s observed the positive ethos of this ensemble. It’s evident to anyone who walks into the room.

I chose these people, and I chose well. Watching them grow together as a supportive ensemble this summer was deeply fulfilling.

The Wonder of Watching Actors Develop Characters

The dystopian novel that is the source material for this production was never intended to be performed on the stage. That presents a challenge for the actors because they can’t look to past productions for clues about how their characters have been performed by other actors. If we were doing a well-worn play like Twelfth Night, Little Foxes, or Fences, the actors could research past productions to see how other actors approached their roles and decide how they might portray them in a fresh way. No such road map exists.

Additionally, as UATX provost and dean Jacob Howland noted, “We is the greatest dystopian novel of the twentieth century, but also one of the least known.” That means the audience coming to the play won’t know these characters either. Savvy theater-goers know Olivia from Twelfth Night, Regina from Little Foxes, Troy from Fences. They walk into those productions with some expectation about the characters they are going to see and the dilemmas they will endure.

Even if they’ve read the novel, nobody knows what the characters in We sound like because they’ve never spoken on the stage. If audience members have not read the book, they won’t be familiar with the oddly named characters like D-503, I-330 or the Benefactor.

All this presents a challenge for the actors because not only will they have to bring their characters to life, they will have to introduce them to an audience and make the audience fall in love with them.

But they are doing it–fearlessly. More than that, they are making the performances their own.

On the last day of rehearsal, one actor made the subtext of the dialogue he delivered so crystal clear, I nearly cried during his final scene. He brilliantly did what an actor is supposed to do: he used clues in Zamyatin’s purposefully vague text to identify what the character might be feeling underneath the words he’s saying. This actor’s choice was so vivid and strong it blasted right through his scene parter, who I could see was also close to tears. After the scene was over I asked him, “Were you trying to convey… [spoiler deleted]?” and he said, “Yes I was!”

It was such a clever choice on this actor’s part that I was left in awe and wonder. His choice added a twist to the story I don’t believe the audience will see coming, but one that will be deeply satisfying. Even better, I didn’t tell the actor to do this, he took the initiative on his own. It’s a wonderful feeling when your collaborators intuit what the project needs!

I can’t wait to get back into rehearsal with him in September to see how this choice grows in other scenes and how it deepens his unique performance of this character.

Acknowledging and Accepting Abundance

Sometimes when I think about how much work there is still to be done between now and opening night I get overwhelmed. It’s at those times I remind myself this project has already brought an abundance of joy, fulfillment and wonder into my life, and there’s more to come. The rewards I’ve received and the ones that are coming my way are rewards I’ve earned through hard work, and that’s also worth noting. We all deserve to find joy, fulfillment and wonder in our work.

As I conclude this essay, I’m reminded that it’s a choice to pursue these rewards and it’s also a choice to recognized these gifts when they present themselves in abundance. Accepting and acknowledging the abundance of joy, fulfillment and wonder I have received will get me through the tough times yet to come. They will keep me afloat and moving forward with the work, one small step at a time. As Sondheim also wrote in Sunday in the Park with George:

The art of making art Is putting it together Bit by bit.

Thank you for reading. I’ll keep you posted on how things progress and I look forward to seeing you at the theater October 11 - 20, 2024.

WE is made possible by grant funding from the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR) in the Arts, the Puffin Foundation Ltd., and NYSCA-A.R.T./New York Creative Opportunity Fund (A Statewide Theatre Regrant Program). Production design support provided by the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Design Enhancement Fund, a program of the Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York (A.R.T./New York).