Where We Started with WE

How seeds from the first production meeting blossomed into the play.

Independent theater provides opportunities for artists like myself to bring unique and groundbreaking work to life, offering a stage for voices that might otherwise remain unheard. By championing independent theater, you can nurture a vibrant ecosystem where creativity thrives and varied perspectives enrich the performing arts.

In a prior essay, I wrote about the design concept for the adaptation of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1920 dystopian novel WE I’m directing and producing this fall. Although I began developing scenic ideas with my collaborators in the summer of 2022, our first in-person meeting for the project wasn’t until October 2023.

While I appreciate the convenience of Zoom, virtual meetings are simply not the same as meeting in person. Finding a time when six busy New Yorkers could meet “IRL” took some finagling, but it was well worth the effort–there’s no substitute for the vibrant creative spirit that circulates among artistic collaborators in the same room. On that fall afternoon, I was delighted to finally be with everyone and eager to get our artistic engines in gear.

Our agenda included setting a timeline for the project, working backward from opening night, which was over a year away. Also on the agenda was discussion of our two previous productions to identify strategies and techniques we wanted to repeat as well as addressing areas for improvement.

One approach everyone agreed supported us well was scheduling working periods followed by reflection periods. We discovered this approach by accident, it happened when projects were delayed or derailed for various reasons, but the delays revealed a useful strategy.

Since we create productions starting with source material, we don’t know on day one what the play is, or what its needs and wants are. All that exists is a hunch that this source material has potential. We don’t know how many actors are need, if the show will have puppetry, or if there will be fake blood on stage. In the early days, it’s more questions than answers, but an extended timeline provides space between rehearsal periods to uncover creative solutions. For that reason, we schedule working periods during which we experiment in a rehearsal room with actors, followed by reflection periods for production meetings between myself, the designers and the production stage manager. In reflection meetings we think through what we discovered while working with the actors and strategize what we need to do in the next working period.

On that October afternoon, we decided in 2024 we’d hold a Winter Experimental Lab for testing rough ideas, a Spring or Summer Workshop to solidify the piece, and a Final Rehearsal Period in the fall to refine the play before technical rehearsals in the theater began in early October 2024.

Looking back eleven moths later, I’m proud to say we made our way through the Lab and the Workshop with gusto. We’re about to begin the refinement rehearsals, and as I prepare for the final sprint, I wanted to take a backward glance at ideas for the play that emerged from an activity we did at that meeting.

A Brainstorm Of Interests and Excitements

I was excited to adapt WE into a play because its central story about a person discovering he’s been robbed of his humanity by orthodoxy and propaganda deeply resonated with me. But I wanted to know what (if anything) in this novel interested or excited my collaborators.

There were several reasons for this. First, good novels reveal different stories to each person who reads them, and I was curious to know what resonated for everyone else. I was even more curious to know if they observed things in the book I did not. I wanted to hear as many viewpoints as possible. I also had a mild case of uncertainty, wondering, “Am I the only one who’s interested in this book from 1920? Does it have anything to do with our lives in the 21st century? Am I out of my mind?” Finally, I thought simply asking everyone about their interests and excitements would spark conversation and get us energized by our collective creativity.

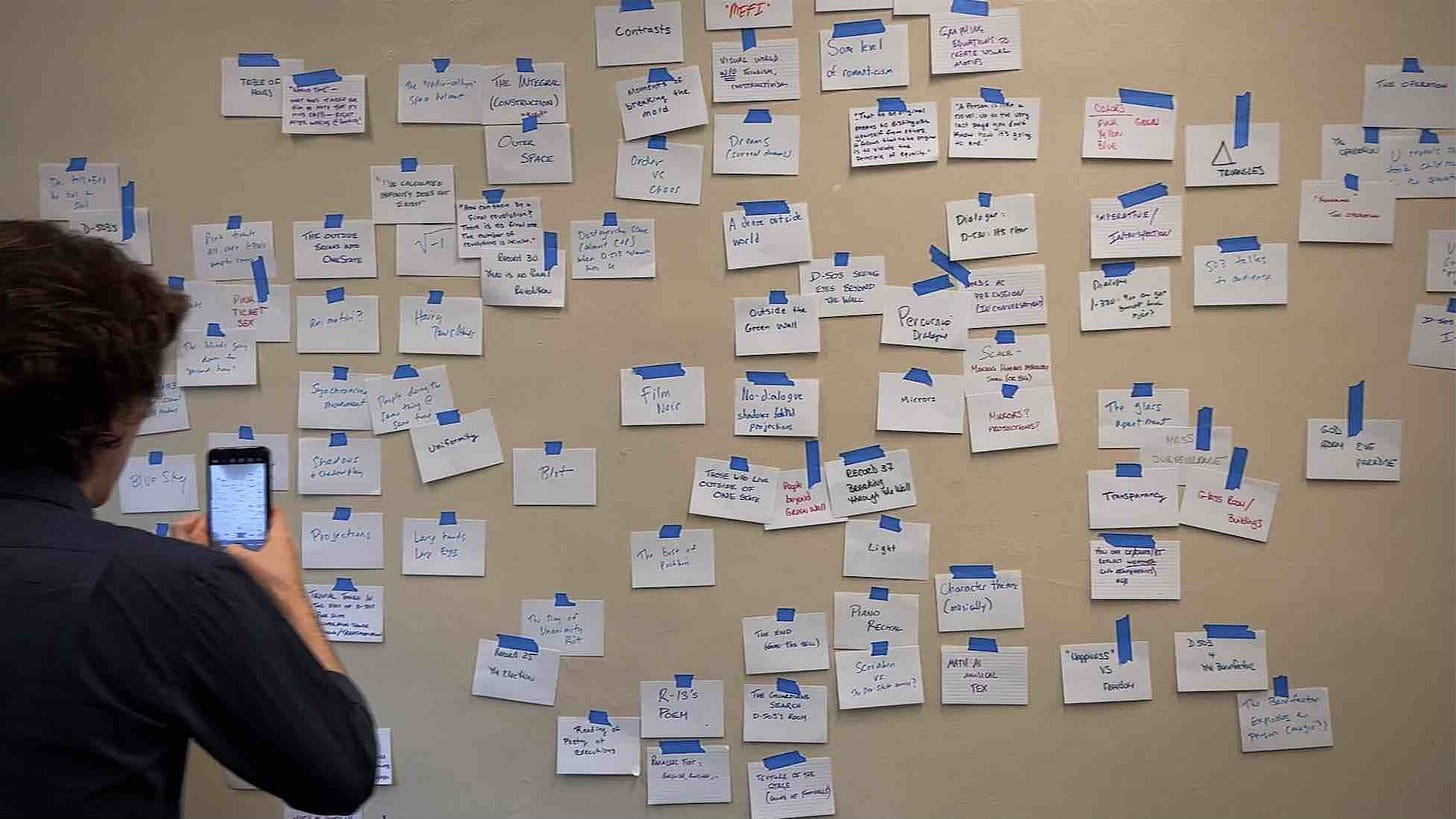

To find out, I gave everyone index cards and asked them to write down anything they might be interested or excited to see in a theatrical adaptation WE. I told them to write one idea on each card. I explained they could identify a specific moment from the plot, a line of dialogue, an object, a projection idea, a setting, a character, a color, a sound, a gesture, anything they would be excited to see on opening night. I also said they didn’t have to limit their ideas by discipline, e.g. the costume designer didn’t have to contain her responses to fabrics and textures, she could write about music, movement sequences, lighting, anything that interested her.

After we wrote, we used blue painter’s tape to attach the index cards to the wall (see photo above). Then we took a silent gallery walk to read all the cards. I then asked my collaborators to identify something on a card that they didn’t write, but that also interested or excited them.

As shown in the photo above, there was no shortage of interest and excitement cards. Through this activity and our subsequent conversation, I found out I was not an artistic lunatic after all and adapting WE was a fantastic idea.

SPOILER ALERT!

If you don’t want to know what happens in WE, read the rest of this essay after the show. If you don’t want to read ahead, but want to see the behind-the-scenes photos below, follow me on Instagram or Facebook.

That being said, most people know what happens in Romeo and Juliet before walking into the theater and enjoy the performance anyway. I don’t think what I’ve written below will ruin anything. In truth, knowing how the show was created may enhance the experience.

Sound good?

Then onward!

Many of the cards we made are captured in the picture above. They aren’t easy to read in the photo, and I won’t relay them all, but here are selected responses that were significant. They broke down into a few categories:

Settings or moments from the story:

A city made of glass-a surveillance state The piano recital R-13’s Poem The operation

Items that appear in the story:

Old world objects Mirros Pink Tickets for Sex

Lines of dialogue that resonated:

"It is too bad... it appears you have developed a soul!" “To be original means to distinguish yourself from others. It follows that to be original violates the laws of equality.” “How can there be a final revolution? There is no final one. The number of numbers is infinite.”

And possible stylistic ideas:

Dreams Film Noir Scale Uniformity Synchronized movement Some level of romanticism

Looking back on our interests and excitements eleven months later, I’m astonished by how many of these ideas made it into the play. Sadly, the piano recital scene met the cutting room floor in the aftermath of an eternal invited presentation of Act I, but the other ideas are very much alive. I’ve highlighted three that were especially fun to work on.

R-13’s Public Execution Poem

The characters in WE don’t have names, they have numbers. The protagonist is the mathematician D-503. R-13 is his best friend, possibly because he is the polar opposite of D-503, he is a poet. Or, to be more precise, a poet in service to the One State.

R-13 has been tasked with putting a death sentence into verse for a public execution. We were excited about hearing this poem during the execution scene, but to my dismay, Zamyatin did not include the text of the poem in his novel. Thanks Yevgeny! Further, he describes the poem as written in “sharp, quick trochees–like the blows of an axe.”

For readers unfamiliar with Shakespeare, a trochee is one unit of poetic meter featuring a stressed syllable followed by an un-stressed syllable. You may recall the trochaic verse in Macbeth:

Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

I’m not a poet, and the idea of writing a poem scared me. So I attempted what I thought was a crafty work-around. I tried to suggest a poem during the Winter Lab. I asked the actor playing R-13 to read fragments of poetic lines that came and went in between moments of staging and music. I envisioned a cinematic effect of fading in and out, but it didn’t work.

R-13 needed a proper poem that told the audience another poet committed a crime by speaking out against the One State, and that the Benefactor (the head of state) would put things right by executing this heretical poet with his “iron” fist.

I knew how the poem had to function in the story, but I had no experience writing trochaic verse. Nevertheless, my back was to the wall, so I took the plunge. After numerous trials and errors, here is what I landed on:

His Hand will fall on he who strayed the Fool who dared to break away a Poet mad with heresy Who spurned sound reason brazenly. For the crime of selfish verses All the Numbers rise to witness How with strong cast iron hand He unifies us all again.

I’m no John Donne; the poem could be better. However, Zamyatin explains the poetry of the One State is not good poetry, it’s useful poetry. The state poets in WE are forced to propagate orthodoxy through their art because that’s useful to the state. For that reason, a blunt poem is just what the moment needs. It’s trochaic(ish), and it gives the audience the information they need to understand the story so, as the saying goes, “It’s good enough for jazz.”

I was scared to do it, but I did it anyway. As Stephen Sondheim wrote in his musical Sunday in the Park with George:

Look, I made a hat Where there never was a hat.

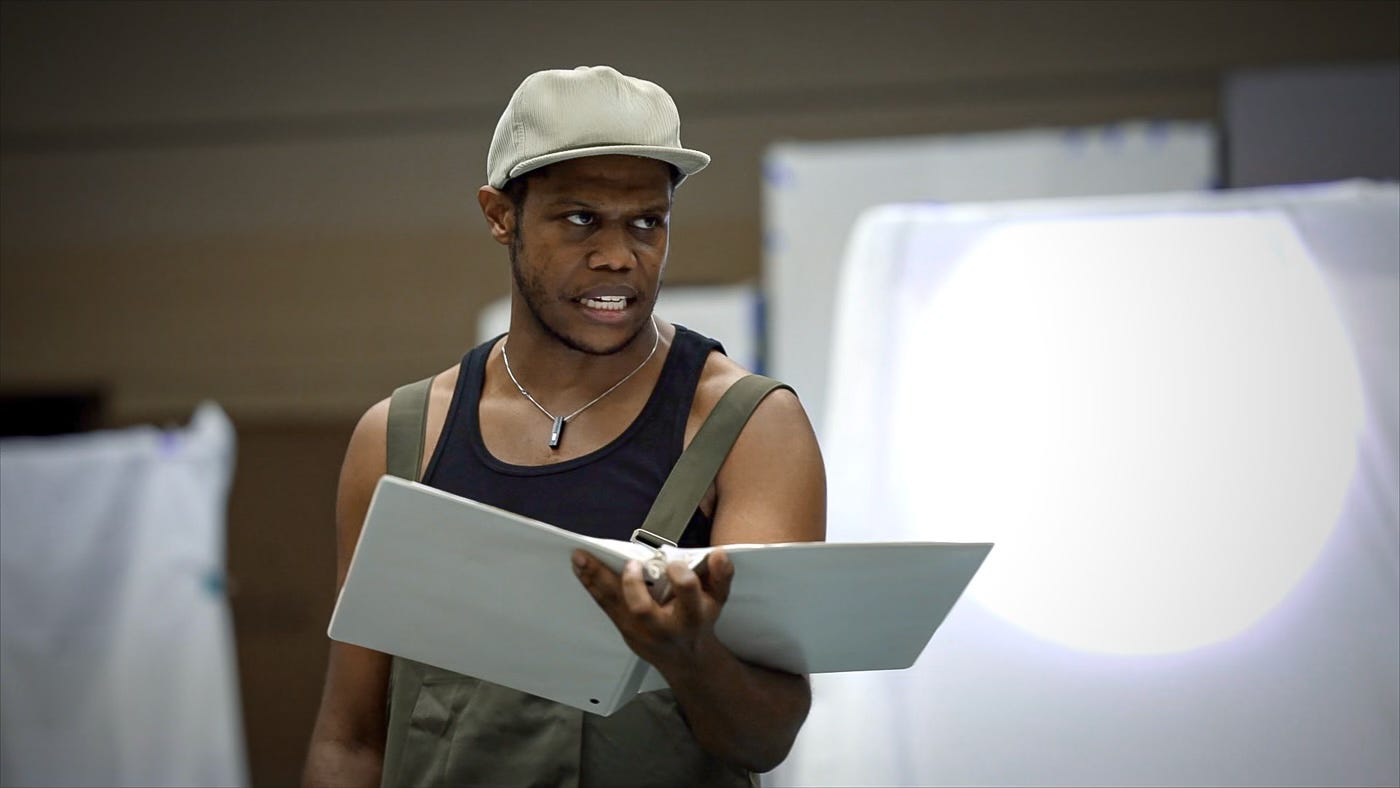

And the actor playing R-13 performs it well!

Film Noir

Zamyatin wrote WE in 1920, decades before the emergence of film noir. But reading the novel, I was struck by its endless use of noir tropes: an outsider recalling the story about his narrow escape from a labyrinthine plot, a femme fatale seduces the protagonist into a knotty ethical dilemma, shadowy figures who may or may not be surveilling the main character ooze out from street corners, a city that seems perfect on the surface hides a dark underbelly, and (of course) cigarettes, booze and sex. For a novel many regard as one that established dystopia, it also seems to have foreshadowed noir.

In addition, the classic noir film Gaslight doesn’t hold a candle to the level of deception in WE. Citizens of the One State are told individuality “violates the laws of equality”, imagination is a medical condition akin to epilepsy, and many voluntarily submit to a surgery that supposedly “removes the center of imagination” from their brains!

The challenge of infusing a cinematic style into a live theater piece excited me. I’ve had a glorious time exploring how noir can be expressed in the show-as you can see from the photo below, there’s been lots of success playing with flashlights! I was delighted when an actor incorporated a private moment in which his character was seen smoking during a scene transition–he didn’t tell me he was going to add this, he just did it, which was a fun surprise–I loved it! I’m looking forward to seeing how the lighting and projection designers amplify the show’s noir moments during technical rehearsals next month. No doubt the shadows will expand!

Romance & Pink Tickets for Sex

The authoritarian regime of WE attempts to regulate everything in the One State, including love. As D-503 relates, love is considered an antiquated nuisance:

The thing which was for the ancients the source of innumerable stupid tragedies has been converted in our time into a harmonious, agreeable and useful function of the organism, a function like sleep, like physical labor, the taking of food, digestion, etc.

In the novel, the state devises a system whereby citizens report to a “Sexual Department” and “register” for the “services” of anyone they choose. Upon registering, citizens are given a pink ticket permitting intimate activities behind lowered curtains.

What could go wrong?

A love triangle smolders between D-503, his best friend R-13 and O-90, the woman they are both registered to; an unsanctioned affair ignites between D-503 and the rebellious I-330; all the while U-, a woman who works the front desk in D-503’s building, burns with not-so-hidden desire for him.

Drafting a script that allowed the audience to clearly track these intertwined affairs was tricky, but having everyone in the room to try out versions of the play this summer made it easier to see how we could clarify the relationships.

As I mentioned earlier, I cut the piano recital scene from early in the story because it had a fantasy moment in it that showed D-503 and I-330 dancing together which killed the sexual tension between the characters–it was too early in the play to see them touching, if they danced together at the beginning, we had nowhere to go. Although I loved the scene, it had to go, but we’ll always have the photo of it below.

Sex is front and center in Zamyatin’s novel, and I was worried we might not find a way to express intimate moments with style and tact. But as you can see from the photo at the beginning of this section, we’ve had success creating sensual moments in silhouette that are far more powerful than they would be if shown realistically. And wait until you hear the music our composer has written for these moments!

Entering The Final Stretch

There were plenty of other interests and excitements from October 2023 that I haven’t commented on here, but if you come to the show, you’ll see them on stage!

As Mirra Ginsburg writes in the introduction to her 1972 translation of WE, Zamyatin supplied mounds of rich material to work with:

It is a complex philosophical novel of endless subtlety and nuance, allusion and reflections. It is also a profoundly moving human tragedy, and a study in the variety of human loves (passion: D-503; domination: I- 330; jealousy: U; tenderness, and gentle, total giving of the self: O-90).

I love making theater, and I hope Zamyatin loves this production, wherever he may be.

Our last rehearsal period begins this weekend. I’ve missed the cast and creative team over the last few weeks and I can’t wait to get back in a room with them for the final stretch! I’ll keep you posted on how it goes and I look forward to meeting you at the theater!

WE is made possible by grant funding from the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR) in the Arts, the Puffin Foundation Ltd., and NYSCA-A.R.T./New York Creative Opportunity Fund (A Statewide Theatre Regrant Program). Production design support provided by the Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Design Enhancement Fund, a program of the Alliance of Resident Theatres/New York (A.R.T./New York).